Loco Gringo

“Like modern industrial society, the Maya built their civilization on a nonrenewable resource base. In their case it was the fertility of fragile tropical soils, which couldn’t support intensive corn farming forever. On that shaky foundation they built an extraordinary civilization with fine art, architecture, astronomy, mathematics, and a calendar more accurate than the one we use today. None of that counted when the crops began to fail. Mayan civilization disintegrated, cities were abandoned to the jungle, and the population of the Mayan heartland dropped by 90%.”

John Michael Greer – “The Long road down: decline and the deindustrial future”

Writing this month’s post has proven a challenge. I was planning to write an update on the latest twists in the on-going Brexit saga but the truth is that it is difficult to predict the eventual outcome of this drama.

So, I changed my mind.

I hope you readers clocked the recent news story of the successful drone attack on the Abqaiq oil fields in Saudi Arabia, the second largest in Saudi Arabia. Saudi oil supply has been halved as a consequence, oil prices are expected to spike to $100 per barrel and it could take weeks to get supply back to normal.

Imagine if, instead of a few drone attacks, a far bigger attack of Saudi oil facilities occurred and the bulk of Saudi oil supply went off-line for months on end, if not, forever? Could you imagine the economic and geopolitical chaos that would result! In such a scenario you would be wise to stockpile food and other core goods if you haven’t already got your secret supplies sorted.

This is a reminder of how fragile our industrial civilization is to major shocks.

I’ve just started reading a superb new novel, called The Second Sleep, by the brilliant British writer Robert Harris. On the surface, the novel is based in our medieval past among the ruins of the ancient Roman Empire but you realise, within a few chapters, that it is instead placed in our deep future where the Church is dominant, population is a fraction of today’s and we have returned to an era of lords and peasants.

The reason I’ve dedicated this month’s post on Forecasting Intelligence to our deep or far future is that it gives us a sense of perspective on the turmoil of our current era. I have focused on this blog on the likely challenges and trends within the next few decades given that this is what myself and you will be most concerned about since we will be living through them.

However, I probably have not covered in sufficient thought the longer-term fate of our industrial civilisation.

To start with, those readers who find this topic fascinating should read the following books, the Robert Harris one just mentioned, but also John Greer’s “The Long Descent” and “The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post-peak World”. They all provide an interesting fictional and non-fictional guide to the likely pattern of our own civilizational collapse and the potential future civilizations that could arise from the collapse.

Our human history has seen dozens of civilisations rise and fall and there are certain patterns that can be seen across the thread of history.

Our own industrial civilisation, as noted in the quote from a brilliant Greer article on the subject, seems to be tracking closely the Mayan civilisation which had a relatively “fast” collapse. This was because it was reliant on a non-renewable resource, fertile soil, in a similar way we are reliant on non-renewable fossil fuels.

There are not unlimited supplies of oil, gas and coal to sustain our civilisation for thousands of years to come and the consensus is that within decades we will be facing major supply problems, in particular oil.

And it isn’t just fossil fuels. Phosphate is a critical fertiliser that underpins the global food system which, if continued to be consumed at current levels, will be in critical shortages by 2040. Now, I would expect a degree of mitigation, adaptation and eventually strategic restrictions on the supply to global markets of such a strategically vital resource so it is unlikely to run out within twenty years. However, it is likely, given that the world population is likely to grow for at least another decade that demand for this critical resource will continue to grow for the foreseeable future.

Major supply problems for phosphate, geopolitical tensions over access and potentially even resource wars, are looking probable by the 2040’s. And that is just one non-renewable resource challenge the world is facing.

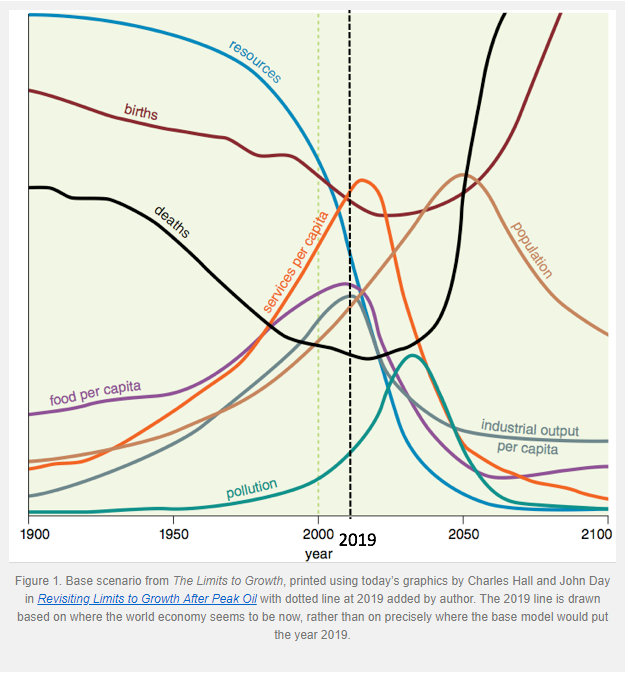

So where is all this taking us? My understanding is that our civilisation will peak, decline and collapse into a deindustrial Dark Ages within 150 years or so. Evaluating when we peaked as an industrial civilisation is a tricky art but the business-as-usual Limits to Growth modelling, which I originally reviewed here, indicates a global peak around 2020.

Our finite world

There are alternative arguments, that within specific countries peaks occurred earlier. Greer himself argues that the United States peaked in the late 70’s in terms of energy per capita. For the sake of simplicity, I will go with a global “peak” which would indicate that our civilisation will end, 150 years from now, around 2170 AD.

How does this macro, and let’s be honest, slightly terrifying analysis, translate into our lives and perhaps more importantly our children and grandchildren who will bear the burden of handling this descent into a future Dark Ages?

This beautiful quote from John Greer describes the fate of a three generational American family over the next 150 years or so and it is a good description of any on our future destiny.

“Imagine an American woman born in 1960. She sees the gas lines of the 1970s, the short-term political gimmicks that papered over the crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, and renewed trouble in the following decades. Soaring energy prices, shortages, economic depressions, and resource wars shape the rest of her life. By age 70, she lives in a beleaguered, malfunctioning city where half the population has no reliable access to clean water, electricity, or health care. Shantytowns spread in the shadow of skyscrapers while political and economic leaders keep insisting that things are getting better.

Her great-grandson, born in 2030, manages to avoid the smorgasbord of diseases, the pervasive violence, and the pandemic alcohol and drug abuse that claim half of his generation before age 30. A lucky break gets him into a technical career, safe from military service in endless wars overseas or “pacification actions” against separatist guerrillas at home. His technical knowledge consists mostly of rules of thumb for effective scavenging, cars and refrigerators are luxury items he will never own, his home lacks electricity and central heating, and his health care comes from an old woman whose grandmother was a doctor and who knows something about wound care and herbs. By the time his hair turns gray the squabbling regions that were once the United States have split apart, all remaining fuel and electrical power have been commandeered by the new governments, and coastal cities are being abandoned to the rising oceans.

For his great-granddaughter, born in 2100, the great crises are mostly things of the past. She grows up amid a ring of sparsely populated villages surrounding an abandoned core of rusting skyscrapers visited only by salvage crews who mine them for raw materials. Local wars sputter, the oceans are still rising, and famines and epidemics are a familiar reality, but with global population maybe 15% of what it was in 2000, humanity and nature are moving toward balance. She learns to read and write, a skill most of her neighbors don’t have, and a few old books are among her prized possessions, but the days when men walked on the moon are fading into legend. When she and her family finally set out for a village in the countryside, leaving the husk of the old city to the salvage crews, it never occurs to her that her quiet footsteps on a crumbling asphalt road mark the end of a civilization.”

Only a lucky few, will escape the burden of poverty within neo-feudal conditions a century or so from now when our future descendants take the path described by John in the early 21st century away from the ruined cities to the villages.

In a world of warlords, military strongmen and neo-feudal aristocrats who own the future means of production (arable farmland, mines and traditional property in our towns and cities) it will be challenging, to say the least, to carve a profitable niche for our future families.

It is not impossible though. And it has been done before.

For those inclined, I would recommend acquiring arable farming land and good quality traditional property stock (e.g. pre 19th century) within those places within the world more likely to survive the coming collapse largely intact.

That could be in central-eastern Europe, Canada or parts of the far East. I would probably avoid the bulk of central America, north Africa and the greater Middle East, along with southern Europe and India given the likelihood that these areas of the world will be rendered uninhabitable by climate change or hugely impacted by the climate migrations, violence and chaos coming.

For those whose ambitions are more modest (and probably more sensible as a result), I would stick to the tips outlined recently in my post on the coming collapse of market economies. Most importantly, the key is to be useful in a world of the future and that will acquire learning, or to be precise re-learning, skills and traditions that have been lost in the developed world.